THE DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN ISSUE #30

18/Jan/2017

EXCLUSIVE GLOBAL REPORT: How To Build Your Audiences (Part 3)

This is the third of a series of global reports on how European filmmakers are blazing new trails on the frontiers of distribution. The first is DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN #28 and the second is DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN #29.

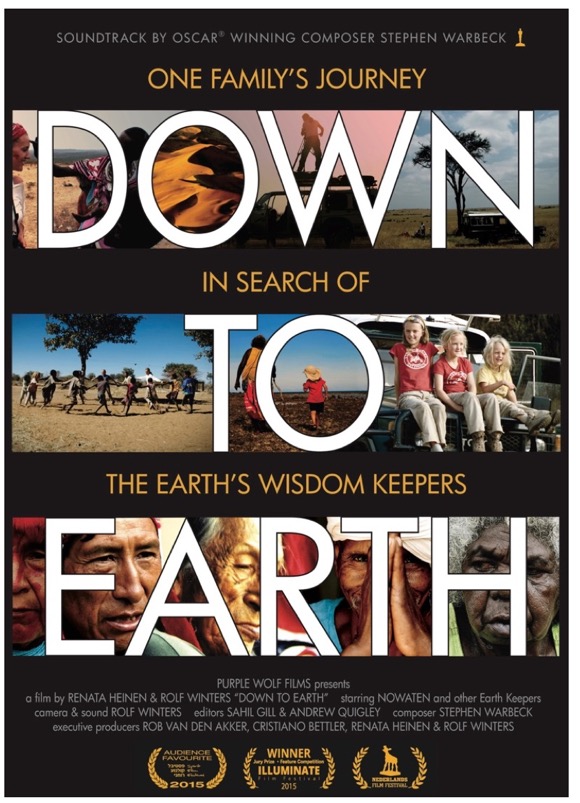

DOWN TO EARTH

In 2005, Dutch couple Rolf Winters and Renata Heinen decided to leave the rat race behind. Seeking to live closer to nature, they left their hectic professional lives in Amsterdam and moved their children to Northern Michigan, where they built a house in a halcyon rural environment. They connected with a clan of Native Americans who lived nearby. Rolf and Renata were so inspired by the wise man Nowaten (“he who listens”) that they began filming their meetings with him.

Compelled to continue “recording the wisdom of the elders,” they embarked on a global journey to seek out other wise men and women and make a film that embodied their world views. They were determined to make the film without a crew, convinced that as a family they could earn the trust of “earthkeepers,” who had never been filmed or interviewed before. Rolf and Renata and their three children set off with 5 backpacks and 5 cameras. For a year, they travelled to six continents, lived in many different tribal communities, and filmed their elders.

When they finished their journey, they moved to the UK, where they spent five years editing the film and working on the music. In 2015, DOWN TO EARTH premiered at the Illuminate Film Festival (an exciting new festival of “conscious cinema”), where it won the jury prize. They next did their international premiere at COP21, the climate change summit in Paris.

Then Rolf and Renata accepted an offer for distribution in France, where the film was released theatrically by an experienced French distribution company. Unfortunately it quickly became clear that the film’s true potential could not be achieved using Old World of Distribution methods. A conventional release with weeklong bookings in cinemas didn’t give the film the chance to build sufficient awareness among its natural core audiences. While the filmmakers glimpsed the film’s potential in France as they gained the support of well-connected allies, they were very frustrated that they couldn’t seize the opportunities that presented themselves because their distributor was afraid it would undercut the release plan. As Rolf lamented, “we felt straightjacketed. We were restrained from doing what the film was made to do—help individuals, communities, and organizations evolve.”

In the Netherlands, the filmmakers have been wildly successful using a New World of Distribution strategy. They began by partnering with a Dutch magazine, Happinez. Rolf’s 94-year old aunt told him about the magazine, which has 200,000 readers in the Netherlands. It ran a glowing piece on DOWN TO EARTH and sponsored eight sold out screenings for its readers, creating a contingent of 2500 enthusiastic viewers eager to share their opinions online and off.

The filmmakers became confident they could release the film theatrically themselves in Holland. They planned to do single special event screenings in theaters rather than playing five times a day every day. After getting a lukewarm response from most Dutch exhibitors, they were able to convince three theaters to book several screenings of Down to Earth. Each screening sold out as soon as it was announced. At first, the filmmakers were only able to book weekend matinees. Theaters were happy because DOWN TO EARTH was selling out and because it was attracting new audiences.

Within three weeks of opening, it was being screened in 30 theatres. They soon sold 10,000 tickets (an exceptional performance for a documentary). By mid-January they passed 60,000 and seem well on their way to 100,000 tickets sold. In many theatres, DOWN TO EARTH was one of its top grossing films for the entire year, even though it didn’t open until October and had many fewer screenings than blockbusters it surpassed. Its per screening average was the highest of the year because so many screenings were sellouts.

In the beginning, Rolf was the only person facilitating discussions after screenings. Within weeks, many people volunteered to lead discussions and 30 people of them were trained as facilitators. When theaters book the film, the filmmakers ask them to schedule slots that are 50% longer so there will be sufficient time for discussion.

Post-screenings discussions have stimulated viewers to enthusiastically spread the word. Some viewers have seen the film multiple times, bringing different friends and family members to experience the film and the follow-up discussions. Many viewers have been very gratified to find strangers who feel the same way they do about the film and the perspectives it presents.

Rather than paid advertising, the film has relied on free press coverage (starting with Happinez and now expanding into mainstream media) and powerful word of mouth. Its core audiences have included people interested in: sustainable living, yoga, spirituality, ecology, educational innovation, corporate social responsibility, and parenting in the modern world. Two-thirds of the audience has been female—from 30 to 80 years of age.

Watch this video to see how DOWN TO EARTH attended Cannes virtually (without ever being there)!

Watch this video to see how DOWN TO EARTH attended Cannes virtually (without ever being there)!

Rolf sees DOWN TO EARTH “not a film to be consumed, but a film to be worked with.” The filmmakers are creating a social enterprise with a “business plan for the future of our children” and have started hiring. The Down to Earth Collective is being designed to facilitate change through shifting consciousness and to empower people at home, at school, and at work. A film festival screening inspired the creation of a new school in Tel Aviv called “the Nurture of Things.” The filmmakers found their own path when they were making the film, and have now found their own path bringing it into the world.

NOTE: I began consulting with the DOWN TO EARTH team in August 2014 while they were finishing the film.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE DIVIDE (see Distribution Bulletin #28), A QUEST FOR MEANING (see Distribution Bulletin #29), and DOWN TO EARTH are different in many ways, but similar in others. For Katharine, for Mark, and for Rolf and Renata, these were their first feature documentaries. Each film was fueled by the passionate beliefs of their teams and their hopes for a better world. Neither formulaic nor generic, each documentary found a unique way to explore its subject.

Although made in the same decade, the filmmakers had no knowledge of each other’s projects. Each project grew organically. Yet they have striking things in common.

Crowdfunding

THE DIVIDE and A QUEST FOR MEANING teams made very effective use of crowdfunding. Their successful campaigns demonstrated their film’s potential, raised a meaningful amount of money, and built initial audiences around each film.

Partnerships

All three films developed partnerships that were critically important to their distribution. DOWN TO EARTH found a media partner that not only highlighted the film for all of its readers but also sponsored a series of key screenings that helped launch the film theatrically. A QUEST FOR MEANING partnered with an important association that had a large membership and chapters around France that could support screenings. THE DIVIDE approached many potential partners early and then had the time to build meaningful relationships with a small number of organizations committed to supporting the film’s distribution.

Theatrical Release

All three films took the same innovative approach to screenings, (after DOWN TO EARTH'S misstep in France). Rather than working with experienced distributors, the filmmakers released their films theatrically themselves – one screening at a time. They avoided the seductive trap of playing theaters a week at a time and thus avoided the fate of most documentaries these days - playing to tiny audiences at most screenings and losing money. By using a single screening strategy, they could focus their promotional efforts and increase their chances of having full houses. They supplemented theatrical screenings and expanded their reach by encouraging organizations and individuals to do screenings in nontheatrical venues.

Special Events

Each team wanted their film to be experienced as a special event rather than simply seen at an anonymous screening. That’s why the filmmakers attended as many of the screenings as they could; if they weren’t able to be there, they often arranged for other people connected to the film or the content to attend. The goal was to have a discussion after almost every screening. A discussion can be genuinely interactive, allowing audience members to participate meaningfully. Panels and Q&As are too often top down, allowing only token audience participation.

Each film was a great catalyst for conversation. Many viewers felt part of a community of like-minded people. These discussions enriched their experience of the film and created a greater sense of connection to the film and the filmmakers. They generated word of mouth and increased the opportunity of the filmmakers to take these viewers with them to their next films.

Distribution Team

Each film had a dedicated distribution team. The teams used customized New World strategies rather than formulaic Old World approaches. Each group was able to identify and take advantage of unique possibilities in their country. The teams were small and nimble, with the ability to seize opportunities when they appeared and shift gears quickly to avoid obstacles.

Trusting the Audience

The filmmakers of all three films trusted their audiences. They treated them as intelligent, thoughtful, open-minded, and caring. The films are not manipulative or dogmatic. They don’t attempt to tell viewers how to think or end with a 5-point call to action. Instead, the films ask questions and have faith that viewers will find answers–individually and together.

© 2017 Peter Broderick

This is the third of a series of global reports on how European filmmakers are blazing new trails on the frontiers of distribution. The first is DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN #28 and the second is DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN #29.

DOWN TO EARTH

In 2005, Dutch couple Rolf Winters and Renata Heinen decided to leave the rat race behind. Seeking to live closer to nature, they left their hectic professional lives in Amsterdam and moved their children to Northern Michigan, where they built a house in a halcyon rural environment. They connected with a clan of Native Americans who lived nearby. Rolf and Renata were so inspired by the wise man Nowaten (“he who listens”) that they began filming their meetings with him.

Compelled to continue “recording the wisdom of the elders,” they embarked on a global journey to seek out other wise men and women and make a film that embodied their world views. They were determined to make the film without a crew, convinced that as a family they could earn the trust of “earthkeepers,” who had never been filmed or interviewed before. Rolf and Renata and their three children set off with 5 backpacks and 5 cameras. For a year, they travelled to six continents, lived in many different tribal communities, and filmed their elders.

When they finished their journey, they moved to the UK, where they spent five years editing the film and working on the music. In 2015, DOWN TO EARTH premiered at the Illuminate Film Festival (an exciting new festival of “conscious cinema”), where it won the jury prize. They next did their international premiere at COP21, the climate change summit in Paris.

Then Rolf and Renata accepted an offer for distribution in France, where the film was released theatrically by an experienced French distribution company. Unfortunately it quickly became clear that the film’s true potential could not be achieved using Old World of Distribution methods. A conventional release with weeklong bookings in cinemas didn’t give the film the chance to build sufficient awareness among its natural core audiences. While the filmmakers glimpsed the film’s potential in France as they gained the support of well-connected allies, they were very frustrated that they couldn’t seize the opportunities that presented themselves because their distributor was afraid it would undercut the release plan. As Rolf lamented, “we felt straightjacketed. We were restrained from doing what the film was made to do—help individuals, communities, and organizations evolve.”

In the Netherlands, the filmmakers have been wildly successful using a New World of Distribution strategy. They began by partnering with a Dutch magazine, Happinez. Rolf’s 94-year old aunt told him about the magazine, which has 200,000 readers in the Netherlands. It ran a glowing piece on DOWN TO EARTH and sponsored eight sold out screenings for its readers, creating a contingent of 2500 enthusiastic viewers eager to share their opinions online and off.

The filmmakers became confident they could release the film theatrically themselves in Holland. They planned to do single special event screenings in theaters rather than playing five times a day every day. After getting a lukewarm response from most Dutch exhibitors, they were able to convince three theaters to book several screenings of Down to Earth. Each screening sold out as soon as it was announced. At first, the filmmakers were only able to book weekend matinees. Theaters were happy because DOWN TO EARTH was selling out and because it was attracting new audiences.

Within three weeks of opening, it was being screened in 30 theatres. They soon sold 10,000 tickets (an exceptional performance for a documentary). By mid-January they passed 60,000 and seem well on their way to 100,000 tickets sold. In many theatres, DOWN TO EARTH was one of its top grossing films for the entire year, even though it didn’t open until October and had many fewer screenings than blockbusters it surpassed. Its per screening average was the highest of the year because so many screenings were sellouts.

In the beginning, Rolf was the only person facilitating discussions after screenings. Within weeks, many people volunteered to lead discussions and 30 people of them were trained as facilitators. When theaters book the film, the filmmakers ask them to schedule slots that are 50% longer so there will be sufficient time for discussion.

Post-screenings discussions have stimulated viewers to enthusiastically spread the word. Some viewers have seen the film multiple times, bringing different friends and family members to experience the film and the follow-up discussions. Many viewers have been very gratified to find strangers who feel the same way they do about the film and the perspectives it presents.

Rather than paid advertising, the film has relied on free press coverage (starting with Happinez and now expanding into mainstream media) and powerful word of mouth. Its core audiences have included people interested in: sustainable living, yoga, spirituality, ecology, educational innovation, corporate social responsibility, and parenting in the modern world. Two-thirds of the audience has been female—from 30 to 80 years of age.

Watch this video to see how DOWN TO EARTH attended Cannes virtually (without ever being there)!

Watch this video to see how DOWN TO EARTH attended Cannes virtually (without ever being there)!

Rolf sees DOWN TO EARTH “not a film to be consumed, but a film to be worked with.” The filmmakers are creating a social enterprise with a “business plan for the future of our children” and have started hiring. The Down to Earth Collective is being designed to facilitate change through shifting consciousness and to empower people at home, at school, and at work. A film festival screening inspired the creation of a new school in Tel Aviv called “the Nurture of Things.” The filmmakers found their own path when they were making the film, and have now found their own path bringing it into the world.

NOTE: I began consulting with the DOWN TO EARTH team in August 2014 while they were finishing the film.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE DIVIDE (see Distribution Bulletin #28), A QUEST FOR MEANING (see Distribution Bulletin #29), and DOWN TO EARTH are different in many ways, but similar in others. For Katharine, for Mark, and for Rolf and Renata, these were their first feature documentaries. Each film was fueled by the passionate beliefs of their teams and their hopes for a better world. Neither formulaic nor generic, each documentary found a unique way to explore its subject.

Although made in the same decade, the filmmakers had no knowledge of each other’s projects. Each project grew organically. Yet they have striking things in common.

Crowdfunding

THE DIVIDE and A QUEST FOR MEANING teams made very effective use of crowdfunding. Their successful campaigns demonstrated their film’s potential, raised a meaningful amount of money, and built initial audiences around each film.

Partnerships

All three films developed partnerships that were critically important to their distribution. DOWN TO EARTH found a media partner that not only highlighted the film for all of its readers but also sponsored a series of key screenings that helped launch the film theatrically. A QUEST FOR MEANING partnered with an important association that had a large membership and chapters around France that could support screenings. THE DIVIDE approached many potential partners early and then had the time to build meaningful relationships with a small number of organizations committed to supporting the film’s distribution.

Theatrical Release

All three films took the same innovative approach to screenings, (after DOWN TO EARTH'S misstep in France). Rather than working with experienced distributors, the filmmakers released their films theatrically themselves – one screening at a time. They avoided the seductive trap of playing theaters a week at a time and thus avoided the fate of most documentaries these days - playing to tiny audiences at most screenings and losing money. By using a single screening strategy, they could focus their promotional efforts and increase their chances of having full houses. They supplemented theatrical screenings and expanded their reach by encouraging organizations and individuals to do screenings in nontheatrical venues.

Special Events

Each team wanted their film to be experienced as a special event rather than simply seen at an anonymous screening. That’s why the filmmakers attended as many of the screenings as they could; if they weren’t able to be there, they often arranged for other people connected to the film or the content to attend. The goal was to have a discussion after almost every screening. A discussion can be genuinely interactive, allowing audience members to participate meaningfully. Panels and Q&As are too often top down, allowing only token audience participation.

Each film was a great catalyst for conversation. Many viewers felt part of a community of like-minded people. These discussions enriched their experience of the film and created a greater sense of connection to the film and the filmmakers. They generated word of mouth and increased the opportunity of the filmmakers to take these viewers with them to their next films.

Distribution Team

Each film had a dedicated distribution team. The teams used customized New World strategies rather than formulaic Old World approaches. Each group was able to identify and take advantage of unique possibilities in their country. The teams were small and nimble, with the ability to seize opportunities when they appeared and shift gears quickly to avoid obstacles.

Trusting the Audience

The filmmakers of all three films trusted their audiences. They treated them as intelligent, thoughtful, open-minded, and caring. The films are not manipulative or dogmatic. They don’t attempt to tell viewers how to think or end with a 5-point call to action. Instead, the films ask questions and have faith that viewers will find answers–individually and together.

© 2017 Peter Broderick